April 15, 1927

L adies of Los Angeles! Do your cakes fall? Is your husband weary of tough pot roast? Do the words, "Company’s coming" fill you with dread? Never fear, because Mabelle E. Wyman is here!

adies of Los Angeles! Do your cakes fall? Is your husband weary of tough pot roast? Do the words, "Company’s coming" fill you with dread? Never fear, because Mabelle E. Wyman is here!

Throughout the 1920s, master chef A.L. Wyman answered the questions near and dear to the hearts of Times readers in his weekly column, "Practical Recipes: Helps for Epicures and All Who Appreciate Good Cooking," supplemented by the popular daily feature, "Suggestions for Tomorrow’s Menu." After Wyman’s death in 1926, his widow, Mabelle, immediately took over the columns. Then, she did him one better, announcing free cooking classes to be offered weekly under the auspices of the Los Angeles Times.

Approximately 1000 Angelenos crowded into Wyman’s lecture room at the Southern California Manufacturers’ Exhibit at 130 S. Broadway for the inaugural class on April 15, some of them sitting on window sills and even under the enamel sink on the stage. Within a week, the Times announced that classes would be offered on Tuesdays and Fridays to accommodate the demand.

Domestic science was a relatively young discipline, and like many burgeoning fields, sought legitimacy in its early days by emphasizing the ‘science.’ Nutrition, economy, efficiency, and tidy presentation were prized, sometimes over taste. While this era in culinary history gave us the icebox cake, it also ushered is a parade of congealed horrors like the tomato frappe (the less said of this unholy mixture of condensed soup and iceberg lettuce the better).

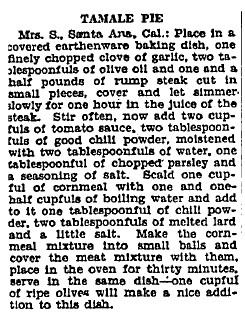

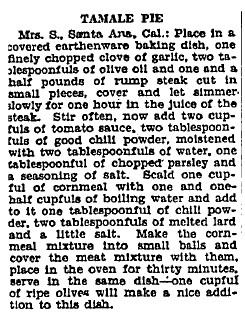

Wyman’s culinary focus was typical for the time, if quirkier. She emphasized meatless dishes, like her Potato and Peanut Sausages, as well as foods grown or produced in Southern California. Popular demonstrations included recipes for Spanish omelettes, cucumber loaf, orange cookies, and the ubiquitous tamale pie.

After the first class, Wyman encouraged her audience to submit questions to a question box, and guaranteed answers either during the next class or in her "Practical Recipes" column. While most columns simply answered requests for particular recipes, others were more cryptic. One can only wonder at the query that prompted Wyman to write, "Mrs. S., Los Angeles: I am sorry but the law prohibits my either printing the recipe you ask for or sending it through the mail." Bathtub julep, anyone?

After the first class, Wyman encouraged her audience to submit questions to a question box, and guaranteed answers either during the next class or in her "Practical Recipes" column. While most columns simply answered requests for particular recipes, others were more cryptic. One can only wonder at the query that prompted Wyman to write, "Mrs. S., Los Angeles: I am sorry but the law prohibits my either printing the recipe you ask for or sending it through the mail." Bathtub julep, anyone?

Wyman seems to have been as good as her word, frequently humoring readers who requested recipe reprints. Despite being demonstrated several times at her lectures, and appearing in A.L. Wyman’s posthumous Daily Health Menus (available for check out at the Los Angeles Public Library), Mabelle printed the recipe for tamale pie no less than 10 times during her tenure with the Times.

The classes remained popular until Wyman’s sudden death on January 23, 1931. She was found at her home at 424 Arden Ave. in Glendale (also the mailing address listed in her column for A.L. Wyman Laboratory Kitchen), having suffered a heart attack. Her estate, including a collection of over 200 cookbooks, was auctioned February 8, 1931.

Recommended reading: Laura Shapiro’s Perfection Salad, a lively study of domestic science and city cooking schools around the turn of the century, and Sylvia Lovegren’s Fashionable Food: Seven Decades of Food Fads, a collection of trendy, eyebrow-raising recipes (including one for the ubiquitous tamale pie).

Also of interest: The Food Timeline, a culinary history project created and maintained by a librarian (woot!), featuring landmark foods trends through the ages. Peking duck to hummingbird cake, it’s all here.

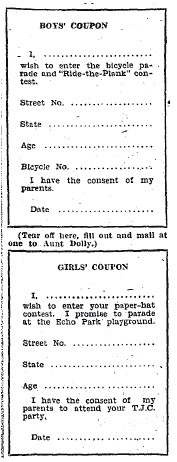

Beginning in 1923, Aunt Dolly’s Page occupied its own corner of the Junior Times, a Sunday supplement that urged young Angelenos to try their hands at blank verse, cartooning, and other feats of skill for fabulous prizes. There were also picnics, parades, community service projects, and a near-constant series of elections for the President of the Times Junior Club

Beginning in 1923, Aunt Dolly’s Page occupied its own corner of the Junior Times, a Sunday supplement that urged young Angelenos to try their hands at blank verse, cartooning, and other feats of skill for fabulous prizes. There were also picnics, parades, community service projects, and a near-constant series of elections for the President of the Times Junior Club

adies of Los Angeles! Do your cakes fall? Is your husband weary of tough pot roast? Do the words, "Company’s coming" fill you with dread? Never fear, because Mabelle E. Wyman is here!

adies of Los Angeles! Do your cakes fall? Is your husband weary of tough pot roast? Do the words, "Company’s coming" fill you with dread? Never fear, because Mabelle E. Wyman is here!

After the first class, Wyman encouraged her audience to submit questions to a question box, and guaranteed answers either during the next class or in her "Practical Recipes" column. While most columns simply answered requests for particular recipes, others were more cryptic. One can only wonder at the query that prompted Wyman to write, "Mrs. S., Los Angeles: I am sorry but the law prohibits my either printing the recipe you ask for or sending it through the mail." Bathtub julep, anyone?

After the first class, Wyman encouraged her audience to submit questions to a question box, and guaranteed answers either during the next class or in her "Practical Recipes" column. While most columns simply answered requests for particular recipes, others were more cryptic. One can only wonder at the query that prompted Wyman to write, "Mrs. S., Los Angeles: I am sorry but the law prohibits my either printing the recipe you ask for or sending it through the mail." Bathtub julep, anyone?