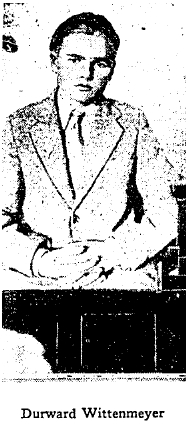

Today, 16-year-old Durward Wittenmeyer confessed to the murder of Fannie Weigel, the wife of a Pomona confectioner. It was just a few days since his release from the Whittier State School, a reformatory. The emotionally disturbed Wittenmeyer said that on his way home from the movies on May 28, he picked up an automobile spring leaf from a scrap heap, and "got a funny notion to hit someone." He saw Weigel walking home from the confectionery story, laden with bundles, and struck her twice in the side of the head. And what was the offense that had previously landed Wittenmeyer in juvie? Throwing a rock at a woman’s head in 1924.

Today, 16-year-old Durward Wittenmeyer confessed to the murder of Fannie Weigel, the wife of a Pomona confectioner. It was just a few days since his release from the Whittier State School, a reformatory. The emotionally disturbed Wittenmeyer said that on his way home from the movies on May 28, he picked up an automobile spring leaf from a scrap heap, and "got a funny notion to hit someone." He saw Weigel walking home from the confectionery story, laden with bundles, and struck her twice in the side of the head. And what was the offense that had previously landed Wittenmeyer in juvie? Throwing a rock at a woman’s head in 1924.

Like a 1927 Veronica Mars, Thelma Sharp, the 17-year-old daughter of a Pomona police detective, helped police pin down the murderer. Working as an usher at the movie theater, she’d seen Wittenmeyer the night of the murder, and knew of his previous antics. When police followed up on her lead, they found Wittenmeyer’s distraught father in the midst of soul-searching. The man burst out, "My boy killed that woman. I have been beside myself since yesterday afternoon when I made him confess to me… I took cleaning fluid and tried to clean the blood off his clothes yesterday afternoon."

Without emotion, young Wittenmeyer confessed to the police. A judge declared Wittenmeyer an unfit subject for juvenile court, and he was set to stand trial as an adult. A psychiatric evaluation found the boy emotionally unstable, but sane. However, a team of alienists for the defense begged to differ. Wittenmeyer suffered from a hereditary form of psychosis, they said, and the boy’s father testified that his wife was known to have hallucinations and that once, she’d been found wandering naked in an orange grove. Supervisors of the reform schools where Wittenmeyer had previously been an inmate testified to his erratic behavior while in custody. Throughout the proceedings, the boy seemed oblivious, amusing himself by arranging blotters on a table.

As the prosecution and defense rested, the jury was instructed to return one of four verdicts: not guilty, guilty of first degree murder, guilty of second degree murder, or guilty of first degree murder with the recommendation of a life sentence. Although deliberations were expected to be speedy, the jury was deadlocked after the first day with a single hold-out for a not guilty verdict, while the remaining 11 jurors stood in favor of the harshest sentence.

After 33 hours, Judge Fletcher Bowron threatened to replace the jurors unless they returned a verdict by noon the next day. However, the jury’s vote now stood at 10-2, with another juror in favor of acquittal. The foreman emerged periodically to ask Bowron whether a recommendation for leniency would be granted, and what the sentence was for second-degree murder. Bowron refused to answer his questions, saying that ultimately, the boy’s sentence was none of their concern.

Finally, after 55 hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict that found Wittenmeyer guilty of murder in the second degree, which carried a sentence of 5 years to life, making the boy eligible for parole in 1932. Acquittal would have sent Wittenmeyer to a state mental facility, so while he did not receive the treatment he needed, the jury’s decision at least spared the teenager from life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Or did it?

As of November 1949 (the last mention I could find of him), Wittenmeyer was still serving time in San Quentin, having been denied parole on at least four occasions.