There’s something perverse and delicious when mundane formality captures genius in its net. The census is one of the best tools for illuminating these queer intersections.

The recently published 1940 US census finds the serial renters Raymond and Pearl (Cissy) Chandler living at 1155 Arcadia Avenue in what was then Monrovia Township. Their monthly rent is $50. (Regrettably, for those who like to visit the residences of great writers, the house has not survived; much of the block was replaced by condominiums in 1979.)

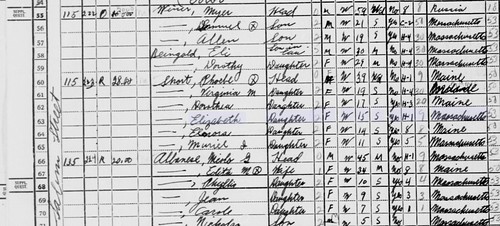

Mrs. Chandler, who answered census taker Cornelius F. Hax’ questions, gives her age as 63 (she was actually 69) and Chandler’s as 51. She states that during the week of March 24-30, 1940, Chandler spent 36 hours engaged in his profession, Free Lance Writer. Yet when asked about employment during the calendar year 1939, she states that Chandler did not work at all.

This report of an idle 1939, like her age, is a lie. Chandler worked fiendishly that year. His first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in February. He began, then set aside The Lady in the Lake and dug into Farewell My Lovely.

By the time the census taker knocked on their door on April 8, the revisions for Farewell were nearly complete; it would be published in October. Perhaps Chandler was in his study working while Cissy spoke with Mr. Hax in the front of the house. Maybe, ever conscious of their privacy, she pulled the door shut behind her and answered his questions on the porch. As is nearly always the case with these dry census records, one is left longing for more. A few facts, most of them wrong, jotted down, and then Mr. Hax was off to knock on another door.

In walking his route that spring day, Mr. Hax recorded a cross-section of the suburban west. The Chandlers’ neighbors came from California, Italy, New York, Nebraska, Wyoming, Ohio, Maine, Pennsylvania, Canada, England, Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Massachusetts, Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota and Montana. There was a painter and a telegraph operator, a chicken rancher and a bookkeeper in a meat packing plant (Chandler, when new to California, had done similar work in a dairy), an automotive mechanic and a U.S. Postmaster, a wholesale shoe salesman, an architect, a department store saleslady, a machinist, a comptometer operator, a stenographer, a teacher, an attorney and a man who kept an aviary.

As he began what would be the most distinguished and lasting literary career of any writer working in the debased genre of detective fiction, Chandler chose to live modestly among strangers, far from L.A.’s literary or intellectual hum. Hollywood wouldn’t call for a few years yet.

The Chandlers kept to themselves. He wrote. She looked after him. He was still sober. They had fourteen more years together. And the purple San Gabriels loomed above.

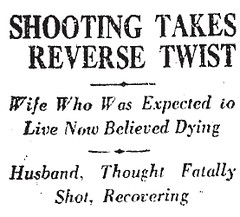

Fred and Lela McElrath had been married for 25 years, and raised three children together, now grown. But just as the couple should have been settling down into contented empty nesthood, a violent disagreement nearly destroyed it all.

Fred and Lela McElrath had been married for 25 years, and raised three children together, now grown. But just as the couple should have been settling down into contented empty nesthood, a violent disagreement nearly destroyed it all.